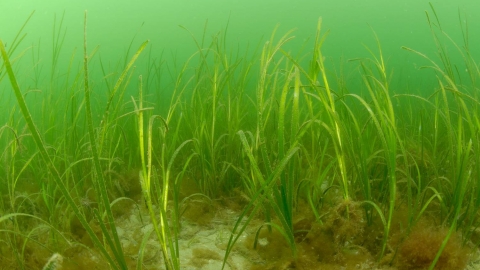

Seagrass ©Paul Naylor www.marinephoto.co.uk/

Seagrass

What is it?

Seagrasses are the only flowering plants able to live in seawater and pollinate while submerged. They often grow in large groups giving the appearance of terrestrial grassland – an underwater meadow.

There are four species of seagrass in the UK: two species of tasselweeds and two zostera species, commonly known as eelgrass.

A natural solution to the climate crisis

Seagrass plants and meadows have the potential to sequester and store huge amounts of carbon dissolved in our seas – this is known as ‘blue carbon’. Similarly to trees taking carbon from the air to build their trunks, seagrasses take carbon from the water to build their leaves and roots (known as photosynthesis).

As seagrass plants die and are replaced by new shoots and leaves, the dead material collects on the seafloor along with organic matter (carbon) from other dead organisms. This material builds up forming layers of seagrass sediment, which if left undisturbed, can store carbon in the seafloor for thousands of years.

Considering that, globally, seagrass captures carbon at a rate 35 times faster than tropical rainforests, and account for 10% of the ocean’s total burial of carbon (despite covering less than 0.2% of the ocean floor), they are one of the most important natural solutions to the climate change crisis.

Why is it like this?

Seagrass is dependent on high levels of light for photosynthesis to grow and can therefore only be found in shallow water to a depth of around 4 metres.

The plants’ roots are anchored in mud, sand or fine gravel, acting to stabilize the seabed and prevent erosion, which has the further effect of helping to stabilise and defend the wider coastline.

The leaves are narrow and long, forming a three-dimensional habitat allowing a wide range of species to inhabit the area. The density of the grasses causes the water currents to slow down and allows nutrients to settle, in turn attracting more wildlife.

Distribution in the UK

Seagrasses are found around the coast of the UK in sheltered areas such as harbours, estuaries, lagoons and bays.

What to look for

The swaying leaves can become covered in algae, anemones and rare stalked jellyfish, while the soft sediment surrounding the roots is home to molluscs, tiny amphipods, polychaete worms and echinoderms.

The sheltered conditions of a seagrass meadow are perfect nursery grounds for young flatfish, and they provide a home for both of the UK's native species of seahorse. At low tide, wildfowl like wigeon and brent geese feed on the exposed seagrass, huge flocks noisily foraging along the shore.

Conservation

A wasting disease was the cause of a drastic reduction of seagrass in the UK in the 1930s. The following recovery has been hampered by increased human disturbance such as pollution and physical disturbance from dredging, use of mobile fishing gear and coastal development.

Sewage discharge high in nutrients is extremely toxic to seagrass, but it also acts to stimulate algae growth which can outcompete the seagrass by reducing the available sunlight. Alien species, including Spartina anglica and Sargassum muticom, also have an impact through competition.

The ability of seagrass to reduce the speed of currents can result in pollutants accumulating in the seagrass bed. Several heavy metals have been found to reduce the plant's ability to fix nitrogen, reducing its ability to survive.

Globally, it's estimated we lose an area of seagrass the size of two football pitches every hour.

30,000km2 of seagrass has been lost in the last couple of decades which is equal to 18% of the global area. The UK has lost approximately 90% of its seagrass meadows, half of which has been lost in the past 3 decades.

Recovery is possible!

If we act now, we can bring our seagrasses back. Despite vast losses of this precious habitat around the UK and globally, there is cause for hope. When damaging activities are removed and seagrasses are given the opportunity to thrive, it can be surprisingly resilient. Not only can they recover from recent disturbances, but seagrass meadows can spread and re-colonise areas of our coast in which they haven’t been recorded in decades.

Research into how conservationists can protect and recover seagrass habitats has begun to yield positive results. Whilst habitat management is not easy in the sea it is possible!

Seagrass restoration projects are being piloted in the UK, with the help of The Wildlife Trusts. Seeds are being collected from various sites and cultivated, ready for replanting to create new meadows. Other work includes looking at mooring systems that reduce the physical impact of boating and educating people around the importance of seagrass.

Fortunately, seagrass habitats feature in a number of our Marine Protected Areas, but designation is just the first step – to ensure their long-term future, appropriate management and monitoring of these sites is essential.

Whilst these meadows may remain unseen by many, they have a crucial role in bringing about nature’s recovery in the sea.